We Are Not a Real Country

An expat stares down NZ's infrastructure week from hell

So the ferry ran aground—but all is not lost. The new classroom at our kids school arrived today!

It's a modular thing, built in four fat slices at a factory in Petone then hauled over the Remutaka Hill in the dead of night. This morning at dawn crews in high-viz orange used a dragon-sized crane to lift each piece off its truck and lower it onto stilts driven into the back playground. A reporter from the local paper was there. Our beloved principal, who’d chased the project’s funding for five long years and was now herself only a week from retirement, teared up in joy. A beaming rep from the building company promised a speedy installation: “It’ll be weathertight by the end of the day.”

One does worry. Lordy, can it rain here; as I type this, poor Hawke’s Bay is flooding again. But I suspect the builder was less worried about the weather than our faith in the construction itself. Anyone would, after this week. For the Americans, let’s run the rap sheet:

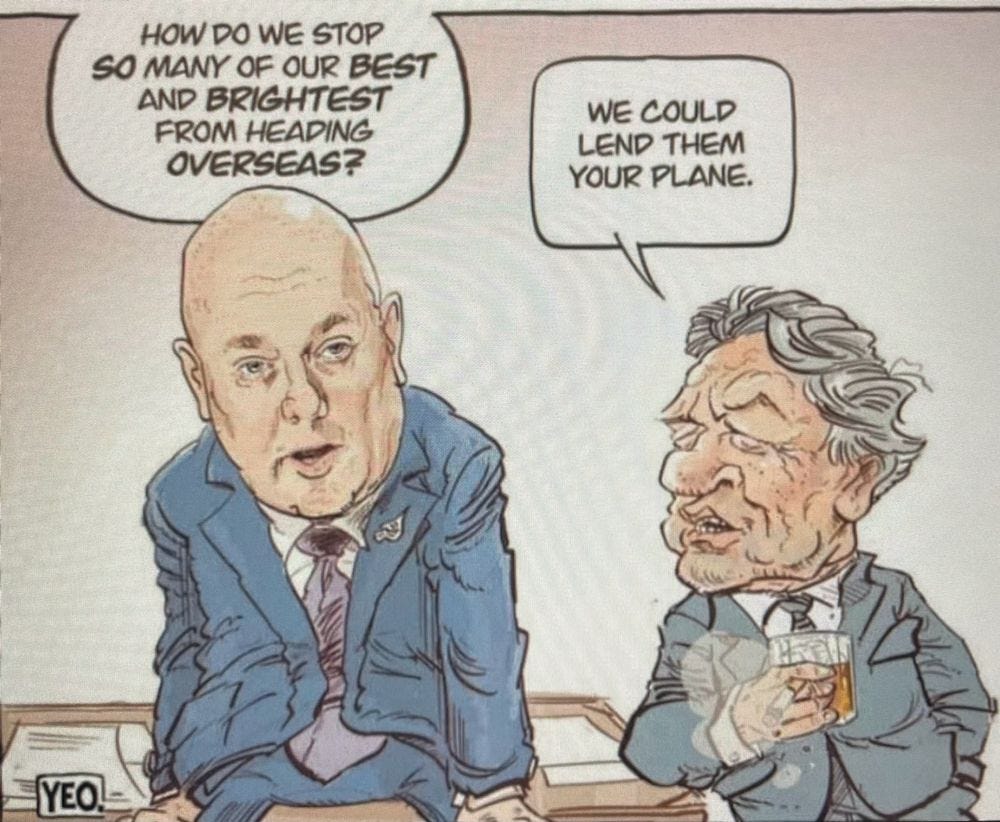

The beloved national metaphor plowed into the shore of the Marlborough Sound, only months after the new conservative government canceled plans to buy new ferries. The prime minister’s ancient plane broke down, again. A power pylon fell over, knocking out power for some 100,000 properties—no weather there, the crew just didn’t screw the bolts back on. Wellington public hospitals are down to single working MRI machine and no plans to buy another. NZTA is spending all its money on road cones. Married at First Sight NZ didn’t even have the budget to put a camera crew at what sounds like a season-highlight first date.

This run of headslappers triggered a round of what you might call national imposter syndrome. A weary AM host Lloyd Burr summed it up: “We are not a real country.”

But the first-person plural is always a question: We who?1

All countries are real, of course. And don’t all countries have their own flavor of essential doubt, their one bogeyman above all? Sea level rise among Pacific nations, say. Coups in Bolivia. Invasion, for any country bordering Russia. Poor Mexico, the Mexicans like to say, so far from God, so close to the United States! Americans, we buy tickets to watch stylish sequels to our own Civil War. New Zealand, routinely left off world maps, worries that it will one day fail to clear some bar of ‘real’ industrialized nationhood—infrastructure, basically, but also the mojo to build it—and slip unremarked into the sea from whence it came.

There’s a famous and possibly apocryphal story that sums the angst up nicely. While U.S. soldiers were stationed in New Zealand during World War 2, the story goes, the Yankee generals offered to put their troops to work building a highway across the North Island, or a tunnel through Manawatu Gorge, or a tunnel under the Rimutaka Hill, or maybe all three. According to legend, the Kiwis turned them down. The story never offers a reason. Everyone knows the punchline, NZ’s unofficial national motto recast in its worst light: She’ll be right.

Whether this actually ever happened is unclear. A Newshub deep dive couldn’t find a smoking gun either way. It’s certainly possible. The States had big empire energy in those days. My own grandfather spent a year paving runways on Okinawa, and I’m pretty sure he didn’t bother to ask.

But the truth hardly matters. The imposter syndrome lingers. Here we’ll call in Eleanor Catton, the semi-exiled Kiwi novelist whose latest book, Birnam Wood, is loaded with zingers about an island nation that drives her crazy as only family can. I’ll pull just one to suggest why the mythic American interstate never happened:

Inconvenience, in New Zealand, tended to be treated as a test of character, such that it was a point of national pride to be able to withstand discomfort or poor service without giving in to the temptation to complain.

Catton’s serving this cold as a June southerly, but there’s a charm here. Kiwis are proudly unfussy about bad weather or humble food. The iconic Kiwi seaside bach doesn’t even have electricity.

At its worst, though, the pride in withstanding discomfort curdles into a broad contempt for public spending on ‘comforts’ that would rival any Wyoming rancher. When I worked for the library service here, there was an old bloke who used to tease me for using the council Suzuki to haul boxes of books between branches. Just ride your bike, he’d hiss through a hard squint, joking but not. When Martinborough tried painting a street mural designed by local school kids, locals mad at a recent tax hike physically threatened the painting crews. Turns out both major parties have pondered buying a new prime minister’s plane for years, but neither pulled the trigger for fear of the “inevitable blowback.”

For the Americans, meanwhile, here’s Alistair Cooke, BBC gadfly and future Masterpiece Theater host, writing his famous Letter from America not long after the U.S. would’ve made the fabled offer. For English, swap in NZ:

One of the irritating troubles about Americans, in violation of the best advice of the best English divines, is that they just don’t believe that whatever is uncomfortable is good for the character.

I’ll spare us the American hyperconsumption sermon here. I’ll just say that my dear family, visiting me in Greytown in a wet July, wondered aloud about the day “when you live in a house where you don't need to wear a jacket inside.” They ain’t wrong. Come home, prodigal son, and claim your birthright of comfort!

Ah, but roughing it is part of the expat’s joy in New Zealand. I grew up next to freeway; I’m glad the GIs never built one here. Instead, this country—particularly the rural stretches where I live and holiday—feels to me like an extended summer camp in Vermont. The roads are two lanes, the bridges one, the parking lots tiny, the beaches empty. Trash cans are scarce. Streetlights are dim. Kiwis turn their heat off at night, and we do too. As a Brit friend of mine here once confessed: “I didn’t move to New Zealand to hear traffic noise.”

But there are ugly vibes underneath here. Am I celebrating an admirable Kiwi simplicity, or vibing on its sometimes painful lack of development?

Both, I’m afraid.

If I was filing this from, say, Mexico, wouldn’t I just call it, well, poverty?

In Mexico, I’m ashamed to say, I could tell myself they were the poor ones. Not we.

New Zealand, for Americans, falls into an uncanny valley. In Mexico I washed my clothes by hand in my landlady’s concrete tub. In Shanghai we had a nanny and a cook. Here in the Wairarapa I’m never sure where on the scale we’ve landed. We do weekend afternoons at a posh Martinborough winery, then come home and wipe the black mold from our windows.

And it’s not that infrastructure and values don’t overlap? For a recent school project, our son just made a diorama of a mountain range. Dotting their paper mache slopes he’d installed several tiny backcountry huts. There’s nearly a thousand of ‘em across New Zealand, many built by volunteers, all of them open to anyone who can hike there to spend the night. In America, where we’ve got a donut shop on top of Pike’s Peak, we’d call this socialism.

But there are absolutes here even an expat can see. All humans—we—want working MRI machines, boats that can steer, a classroom warm and dry.

My heart swelled as I watched that slice of classroom float through the morning sky. The classroom is for the Year 7s and 8s. My oldest is now in Year 4. The classroom will be his in three years, if we’re still here. Was my joy its own imposter? Was I proud for them, or proud for we?

Are we a real country, New Zealand and I?

The guys in orange knelt bolted the first piece of classroom down to its new roots in the dewy grass. The massive crane lowered its jaws and picked up the next slice. The morning was getting on. The school bell rang. I kissed my kids goodbye and went home to write.

This was the writer Teju Cole’s Twitter bio for years. He aimed the question at the West, mostly, and it’s been tattooed in my head ever since. Funny to borrow it here for some intra-West confusion, but the logic still holds, and do I so with full & grateful hat tip.

My Kiwimerican family lived in Featherston for almost two years. What I, an American, could never understand was the lack of window screens! We couldn't have lights on at night without every moth and mozzie and who-knows-what deciding to come in and say hello. Forget having the window open and reading in bed or cooking anything fragrant. My favorite was deciding if I wanted to air out the toilet during #2 with an open window (there was no vent fan), or swat away swarming flies. This house was built in 2016 with a toilet that felt like a small step up from an outhouse.

We ended up buying window screens, some magnetic ones that blew off in a strong wind but overall worked. My Kiwi husband was very embarrassed about it, although privately admitted it made our life much better. 100% the Kiwi ethos of being proud of enduring discomfort, even if the solution is as simple as a $20 bit of wire mesh.

Thanks for the article, finally helped me put to words what I noticed all the time living there! With the way the US is trending now, despite our luxurious window screens, we may find ourselves back before too long.

Dan, late comer here but as an Angeleno-expat to Wellington for fourteen years and then back again (primarily for healthcare and supports that we discovered NZ wasn't able to offer him because, well, it's a bit too small and a bit too poor), this article reminded me of all the things that I love and miss about NZ, and all of the things that infuriated me.

NZ is a lovely country, but I almost always describe it as 'a country that desires the social services and infrastructure of Denmark, but with the tax base and tax rates of Greece.'