Bad Dads with a Gun

Breaking the myths that got us here

Too much death for breakfast this week.

I have plenty to say about Tom Phillips, the Kiwi dad who kidnapped his kids and hid them away in the bush for 1,358 days, minus the odd burglary in town. On Monday morning he shot a cop, and now he’s dead.

But I’m running on fumes about Charlie Kirk, an American dad and right-wing activist. On Wednesday afternoon, Thursday morning here in NZ, he was speaking at a university, and someone shot him, and now he’s dead.

When the Phillips news broke I was standing at the kitchen counter in the spring sunlight, packing lunches for my kids.

When the Kirk news broke three days later I was standing at the same sunlit counter, packing lunches for my kids.

Packing lunches can be exhausting. It’s always a performance of hope. The hope that my kids’ days will go well, out in the world without me. The hope that they will grow up strong in life full of friends, mentors, and fresh fruit conveniently sliced. The hope that they won’t get shot.

Fair to say I never liked either of these dads alive. Now their sad, ugly ends are messing with my hope.

Stick around and I’ll find some hope in Barry bloody Crump,1 whose famous New Zealand novel about a dad with a gun I was reading this very same weird week.

But first—the stupid myths behind these stupid deaths.

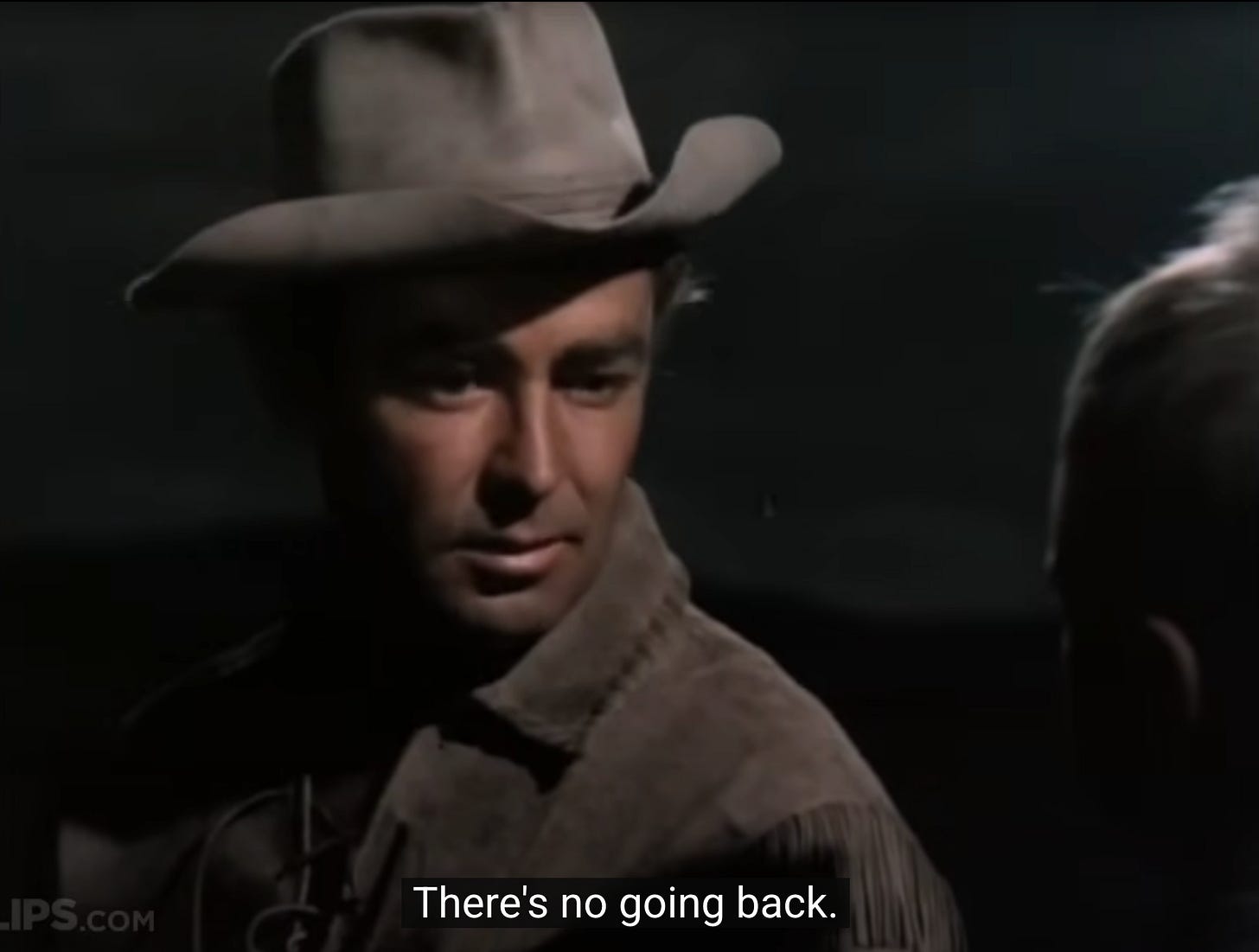

America’s got the Good Guy with a Gun, a lonesome cowboy who dispatches justice with a single shot and then rides off into the sunset. The myth once pretended to have rules: the killing must be done, but it’s cloaked in honor. In the famous final scene of Shane (1953), the myth’s purest distillation, Alan Ladd’s buckskin-clad demi-god delivers what reads now as a dark American prophecy:

Joey, there’s no living with... with a killing. There’s no going back from one. Right or wrong it’s a brand. A brand sticks. There’s no going back.

Joey screams his name again and again but Shane rides off into the bush. The Good Guy with a Gun can never be a father. The Good Guy with a Gun lives outside society precisely so he can nip back in every now and then to shoot a Bad Guy.

Pākehā New Zealand, meanwhile, has the Bad Dad with a Gun. He cares nothing for justice, society, or women, only his own primeval bachelorhood in the Edenic bush of his mind. Three years into the Tom Phillips saga North and South ran a whole cover story detailing its many antecedents in NZ literature and film. Sometimes these legends escape civilization before fatherhood catches them; if they do have kids, their isolation and control is the whole point. From Roger Donaldson’s 1981 film Smash Palace: “She’s my kid and I’ll do what I want with her!”2

Both nations should’ve long since put these stories down like sick lambs.

But they haven’t. Not yet.

The Good Guy with a Gun is one hundred percent the fuel behind America’s gathering dark. Everyone’s a gunslinger, nobody’s a father, and everyone craves a target. We’ve followed a straight, nihilistic line from Shane’s noble regret to Kirk himself declaring that “some gun deaths every single year” were “worth it” to carry on America’s gun-loving dream. They’re not. The latest self-annointed Good Guy just showed us why. The whole mess is stupid, enraging, and deeply sad.

I want to say New Zealand’s maybe a bit farther along? No dad I know here takes Phillips’ side, but that’s a small pool. Kiwi Reddit has been delightfully merciless over a case of Jack Daniels & Cokes spotted at his campsite. But the Bad Dad energy abides. The ugly misogyny still directed at Jacinda Ardern is straight out of John Mulgan’s Man Alone.3 Kiwi Facebook is serving up Pro-Tom AI slop. Even Phillips’ own mayor had to hand it to him:

My goodness, Tom’s shown his resilience over that time, and so have the children.

That’s not resilience. That’s mental illness.

His kids, though—they showed resilience by surviving four years as prisoners of their crazy dad.

Resilience, as it happens, is one of the core values taught at the small rural New Zealand school where my kids eat those packed lunches every day. Kia Aumangea. Be resilient.

Not the false resilience of raising your kids friendless and alone in the mud. Not the false resilience of shooting a cop.

Not the false resilience of Kirk’s racism, bigotry, and smirking support for political violence, no. Not the false resilience of his campaign to harass and intimidate other speakers on university campuses. But never the false resilience of shooting someone as they talk.

I’m talking about the resilience of a physical, spiritual, and emotional sort that one might learn on a tramp through the bush.

I’m talking about the resilience of Uncle Hec and Ricky in Barry Crump’s Wild Pork and Watercress (1986), a novel better known in America for its retelling in Taika Waititi’s 2016 film Hunt for the Wilderpeople. [Spoilers ahead.] Uncle Hec, a stand-in for Crump himself, is categorically a Bad Dad with a Gun. He threatens to “flatten” his adopted nephew all the time, and eventually follows through with a punch. Hec only drags Ricky into Te Urewera, a rugged labyrinth of green hills wedged between the North Island’s volcanoes and its remote East Cape, in the hope that Ricky will give up and leave him alone to fulfill his solo Kiwi fantasy.

Time passes, and miles. Kilometers, whatever. Hec and Ricky count the distance only in streams and ridges. The novel quiets down into an almost zen-like pilgrimage, one the much cheekier film skips past in montage. Old man and man-to-be just walk. They climb cliffs. They name unnamed places. They snag leftovers from backcountry huts. They hunt wild pigs with only their dogs and a .22 rifle. They do weeks-long laps of the hills they know. Months-long laps. My feet hurt just reading. They eat a goddamn kiwi bird. The nation falls away behind them. The cops give up the chase, and other hikers flee them on sight. They have become like ghosts. They are free.

And here’s the key: Unlike Phillips, Hec tells Ricky to decide when they leave the bush.

Ricky waits a few days, makes the call, then out they go, resilient as hell: “We got a few hassles coming up, but we can handle them,” he declares. “We’re okay now.”

I love this quiet subversion of the myth Crump himself wrote and performed for decades. Imagine an American version. Imagine Shane the Good Guy gunslinger telling little Joey—Hey, maybe I’ll stick around and help your dad build this town.4

You can break a nation’s story open.

The Bad Dad can turn good. The Good Guy can put down the gun.

Maybe the lost men will still read it the wrong way. Maybe you can crowd a nation so full of Guns and Good Guys there’s no going back.

I don’t know how either story ends.

But I’ll tell you what. I once got lost in the bush with my son. We were headed back from Totara Flats hut in the Tararua Range. We’d slogged through 9 kms the day before and now faced 9 kms out. He was six years old. I was in over my head. It had rained all night and the Waiohine River had risen over the trail. We walked through the muddy water until we couldn’t follow it any further. There was a moment there on the bank—fifteen minutes, a thousand years—where I could not find the trail. I can still feel that cold rain on my face. I can still see my boy there on the wet river stones, his eyes searching the ridge above us. There it is, he said, and pointed up through the rain at a trail marker I couldn’t see. I follow you, I said, and up we climbed. //

On American anger:

On getting lost in green hills:

Steve Braunias’ phrase, from his review of a 2022 memoir by Barry’s scattered and heartbroken sons. The blunt name does beg a middle epithet.

As quoted in James Borrowdale’s great essay, to which this letter owes a big tip of the battered bushman’s hat. Thanks, James!

The 1939 novel & grim ur-text of Kiwi bushman myth. Skip it and read this great review by Jordan Margetts, written as a man alone under pandemic lockdown.

Add in race here and the reading gets even more interesting. In Crump’s novel, Uncle Hec is Pākehā and Ricky is Māori. There are the odd clumsy lines on this theme but less than I’d feared; the novel is told from Ricky’s point of view and told pretty straight down the middle. There’s a broad but not inaccurate reading of Wild Pork as national allegory, with New Zealand’s indigenous and settler populations moving over the land in silent, loving partnership, culling its invasive species and naming its streams together. Imagine a rewrite of Shane where Joey is not a blonde, blue-eyed kewpie doll but Arapaho or Cheyenne.

I needed to read this today. Thank you. And thank you to all the great Dads out there who love our kids unconditionally ❤️

Great post Dan. Was just reading about Charles Kirk - mercifully I had no idea who he was and even after I did he seemed more of crazed influencer than someone who deserved a moment of silence in the US Senate - but there you go. Good that European Parliament resisted but was disrupted when the Right Wing unsuccessfully attempted the same tribute. We seem to live in a world where increasngly, people celebrate violence - or remain silent in the face of it - for whatever treason; surviving an apocalypse at any cost becomes the goal.

Many people here will still see Tom Phillips as a hero. That he was 'tragically cut down' in front of his own child on Father's Day while providing for his children (by stealing milk and shoes for them) by a police force that many see as a constant enemy will only enhance hs myth. Bar brawls will, inevitably, be fought over this one. - but worse, his children may forever be forced to defend the indefensible, or say nothing, and to never experience their right to even partial anonymity.

So much to think about here - but I held my breath while reading about you and your son being lost - even for moments - in the bush and the importance of that moment when you said "I follow you" and up you both climbed. That will be a moment your son will always remember, of course he will tell jokes, his version of it, at your expense - but honestly that was just the best lesson in resilience, and trust. Well done real-hero Kiwi-American Dad.