You're a White American Dude. Why Did You Leave?

On WADAs, MAGAs, and not wasting your life

The question came without a stinger. A New Zealand writer, one whose work I admire, genuinely wanted to know.

Still, I squirmed. I had no answer. It’s a reductive question, sure, but no more reductive than a blogger calling himself american.nz. Don’t reduce me to a category, I’ll do that myself.

She said man, or maybe male? Kiwis don’t say dude. Dude is our own word. Call me a White American Dude Abroad, or a just a WADA for short.

Yeah, it rhymes with MAGA. It should. We’re not as separate as we wish.

I’d rather answer the question from my own personal timeline. I could just say hey, I read Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses the summer I turned 19, and within a decade I’d hopped the bus to Mexico not once but twice. Romance, adventure, and something to write home about. Next question.

But this is the week Trump halted all international student visas, after moving to block international students enrolling at Harvard. The whiplash here was fierce. Here’s the story when Rotorua’s handsome local hero won acceptance to both Harvard and Princeton. Here’s the story six weeks later when it’s all gone sideways, featuring his same smiling graduation photo. Breaks your damn heart. I hope our man gets there eventually. I hope my country remains worthy of him.

And this is the root of the writer’s question: power. The power I was born to with a WASPy-enough name, white face, Y chromosome, and a crisp blue passport, plus the interest gained through a couple fancy degrees. The power of a university to draw a Tongan Māori kid from Rotorua halfway across the world, and the power that smart young man stands to gain there. The power Trump seeks to hoard for himself and his fellow WADs—that’s the homebound variety—at the expense of everyone else, American and otherwise. There’s a 43-country travel ban in the works. The list tells you all you need to know.

Why, the writer wanted to know, had I left all that money on the table?

I didn’t. I spent it on the chance to roam.

One story of many: we landed in New Zealand in the early days of the pandemic. I was still teaching at NYU Shanghai, a great expat gig I landed entirely through my fancy degrees and social capital (Jenny, a WAWA—White American Woman Abroad—with even fancier degrees than mine, already worked there.) How great a gig? NYU Shanghai ultimately paid for our blisteringly expensive tickets to flee its own campus ahead of Covid—global citizens gotta global—and then kept paying us to teach online from rural New Zealand at our full Shanghai salaries. I held my Zoom-based sections at all hours, including night sessions to reach students across China and the capitals of Europe. Between classes I’d pop down to the nearby dairy for Fanta and licorice ropes. The store was not in the best location, and the shelves were thin. Business seemed slow. I’d grab my sugar fix and chat with the Indian family who ran the place. They were newcomers like us; we chatted about our adjustments to Kiwi ways and I cooed over their baby daughter in the playpen behind the counter. I left NYU Shanghai not long after. We were falling for New Zealand, and we had savings enough that we didn’t scurry back to China to keep our jobs. I found work instead at the local library. One day the storekeep came in to photocopy a stack of documents for his family’s visa application. We chatted about our kids, and then he squared up and asked me straight, one immigrant to another: How did you get a job here? Meaning the library. Meaning anywhere that wasn’t his failing dairy. I chickened out. How long would it take to sketch the web of power and money that had sponsored my wanderings? I’m a WADA, man. I just walked in the door.

But that’s how I left. What about why?

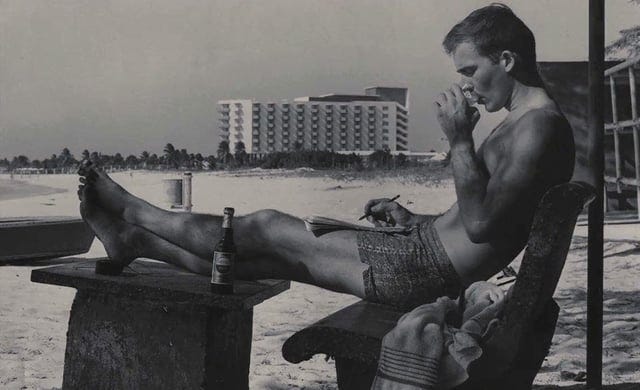

I could say this: I read Hunter Thompson’s letters from South America the summer I turned 20—the early stuff, when he was just a gangly, baby-faced WADA—and thought I oughta do the same.

It’s true. But I was raised on a closer South American story. My grandfather, Norman Crowfoot, grew up in a copper-mining town in Arizona and hungered to see the big, bad world. As a young miner just starting out, he applied for a job in Argentina. We still have the papers—that’s his Argentine work permit above. The company that owned that Argentine mine, hired my grandfather, arranged his draft deferment, applied for his Argentine visa, and bought his plane tickets south—they filed every letter from their headquarters on Park Avenue in New York City.

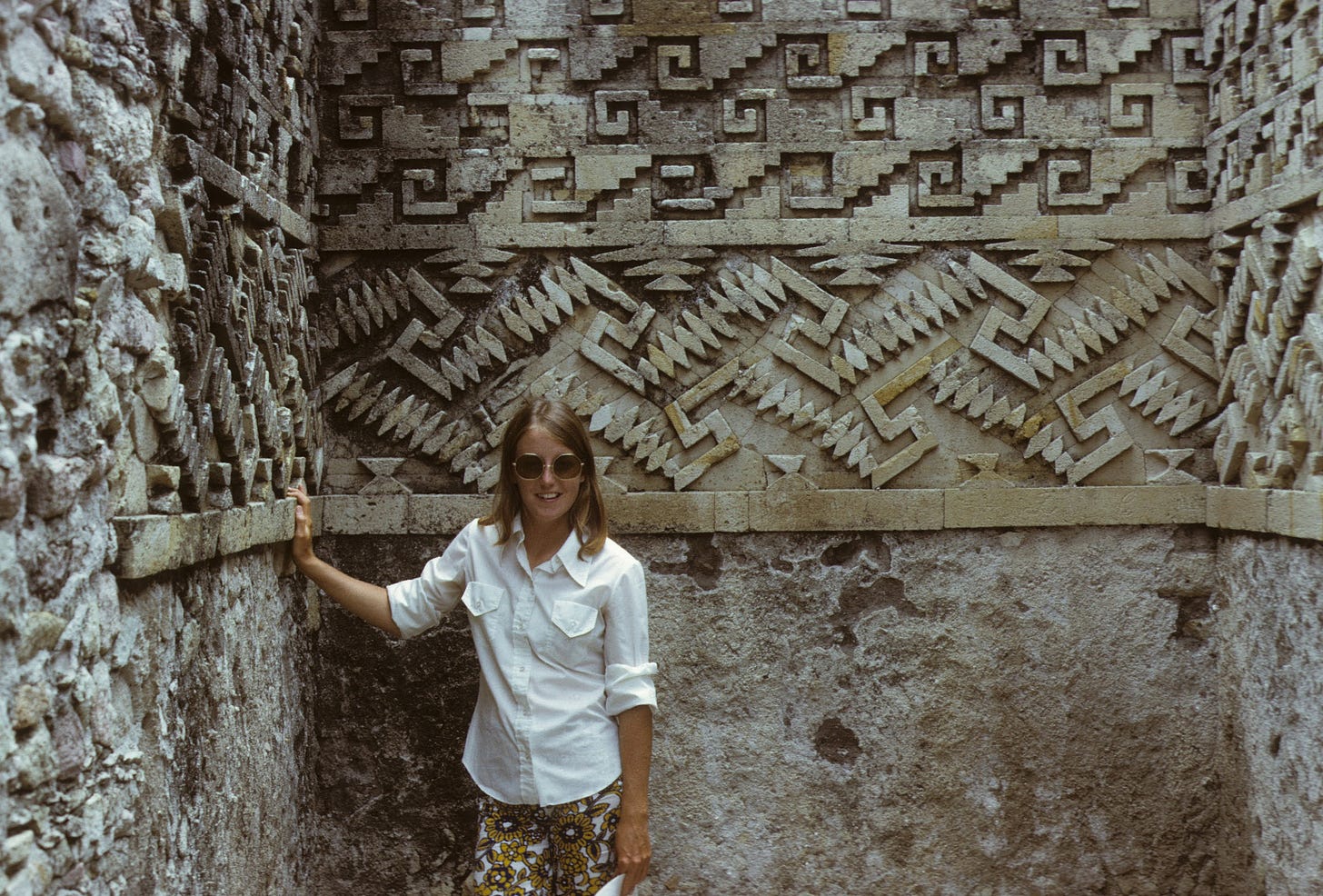

The how becomes a story, and the story becomes a why. My mother, born Melissa Crowfoot, also felt the call to head south. As a grad student archaeologist she joined a summer dig at Monte Albán in Oaxaca, Mexico. My father was another grad student working the same dig. Two white American kids, sent abroad by two American universities, fell in love digging up ancient Zapotec stones. WADA legends and American power abroad are the very reasons I exist.

Fair to protest here that I’m turning wanderlust into a strict expression of systemic power. It’s also just a mysterious ache afflicting humans of any race, passport, or gender. My grandfather’s father, Arthur Crowfoot, left England at age 21 to seek his fortune in America. Once he’d settled down as a dad in landlocked Arizona, he kept a full set of the works of Conrad, inscribing a volume of the letters with an ode to tall ships and the open sea: And down to the sea they must go once more, though they never come back again.

This stuff either moves you or it don’t. Some of us can’t turn it down. As my fellow WADA Bart Schaneman put it in his great recent letter from beaches of Korea: “At least this way you’re not bored.”

You don’t need a WADA story to leave home. Kiwis take their OE. Oaxaqueños have moved en masse to LA. But what bored and restless soul anywhere in the world wouldn’t take the WADA deal?

But there’s a catch.

A WADA at home, if he plays his hand well, will accumulate power. He rises in the ranks, grows the business, builds a network, redoes his kitchen, and becomes an elder in his community. Some of the dudes I admire most in the world are WADs who’ve logged two or three decades now in not just the same city but a single goddamn neighborhood. Grown-ass men, they are.

We prodigal WADAs, meanwhile, burn our inheritance on plane tickets, odd jobs, and field trips to the edge. We spend that coin until we wake up one day as middle-aged foreign exchange students—comfy enough, delighted each morning by the variety of the world, and balancing atop a suitcase life you could tumble with one swift kick.

But hey, at least we’re still WADAs, right?

There’s a reason Substack is chocka with expat blogs. We live everywhere but we run to file here in English, as dedicated expats and nomads. The tell’s in our newsletter titles. Do we name the country we’re writing from? Or do we nod instead at expat life, movement, borderlessness, everywhereness?

I ain’t throwing stones here. Many of these I read regularly and love! Am I any better for naming my home (.nz) while clinging to an American brand? That’s what we’re doing out here. We’re not immigrating, we’re clinging to a life abroad. Because the day we become French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Kiwi—the day we write for our neighbors rather than the terminally American internet—we surrender the last points on that beat-up WADA shopper’s card in our backpacks.

And that’s the question’s real sting: WADAs and MAGAs are hoarding the same power.

How, the writer wanted to know, was I going to tell that story? And why?

I don’t want to overcook this. MAGA abhors immigration because they reject hybridity in any form: fuck ‘em for that alone. Power is always messy, but humans are humans wherever they roam. The line between WADA and local—between immigrant and local—is an infinite and beautiful spectrum, and a story old as stories themselves. We learn by going where we have to go. But we gotta walk that line with grace. As the Kiwis have taught me: always say thanks to your bus driver.

New Zealand, as it happens, is a weird place to write from as an expat. Without a language difference—not much of one, anyhow—my neighbors here were readers from day one. When I started this project I clocked this as an intriguing rhetorical challenge. The deeper I get, I realize what a crazy privilege it is. What new and strange power it’ll give me, as I dare to let the old power fade.

There’s a moment in Schaneman’s letter where he and another WADA are hanging out at a microbrewery in Seoul. My god, have I lived the Shanghai version! The menu straining for some abstract Western ideal. Beery English between near strangers. My Chinese-tuned stomach blown up by a burger and fries.

Bart’s scene is much happier; he’s actually with an old buddy from back home who also lives in Korea now. They’re dads like me, raising kids in a foreign land.

“I stopped using the expatlife hashtag on my Instagram posts,” B. was saying. “One of my friends, this woman I know, kept giving me shit about it.”

Same, B. Turns out she was right.

I read this line and I saw my road ahead, clear as the dirt track down to the Waiohine River. I’m a WAD until I shuffle out of these Texas-born bones. But if I’m still writing an expat blog in ten years, I will have wasted my life. //

As someone who has always yearned to be a WADA but was never brave enough to actually follow through, this essay really hit me in the gut and the heart. I long to know what it feels like to wake up in a different place than the one I’ve known my whole life and have it be more permanent than a two week respite from the grind of being entrenched in everything it means to be American. I didn’t have any wanderlust role models to give me permission, either spoken or unspoken, to follow that path, and I’m sadder for it. Your family legacy of adventure is envious. So glad you took to this Substack experiment!

Also this paragraph - wow: “I don’t want to overcook this. MAGA abhors immigration because they reject hybridity in any form: fuck ‘em for that alone. Power is always messy, but humans are humans wherever they roam. The line between WADA and local—between immigrant and local—is an infinite and beautiful spectrum, and a story old as stories themselves. We learn by going where we have to go. But we gotta walk that line with grace. As the Kiwis have taught me: always say thanks to your bus driver.”

Having taken public transportation last month for the first time in NZ, I sat in the back of the bus and I was amazed at everyone getting off either saying thank you or waving thank you to the bus driver. I commented to Z&R my amazement. ( I liked the rest of your post as well! ;) )